Image

To promote a strategy to address inequities in GI funding, siting and implementation, this project embraces a collaborative, participatory community engagement project to facilitate the design and adoption of GI demonstration projects in the communities, traditionally underserved, low-income communities in southern Tucson. It will involve a robust, participatory process, that is responsive to the needs of the community and can strengthen community cohesion by engaging residents in a meaningful, sustainable way. To address inequities and overcome historic distrust, public engagement must be more than a box checked – and more than a single-focus process that prohibits conversations about complex issues to be discussed, such as health and safety. Further, it needs to be sensitive to community distrust associated with disinvestment or project delays in the community and the potential for participant fatigue. We will explore a variety of engagement strategies, mindful to learn from past experience in the community.

Building from earlier efforts

Several recent reports and processes speak to the needs of the community.

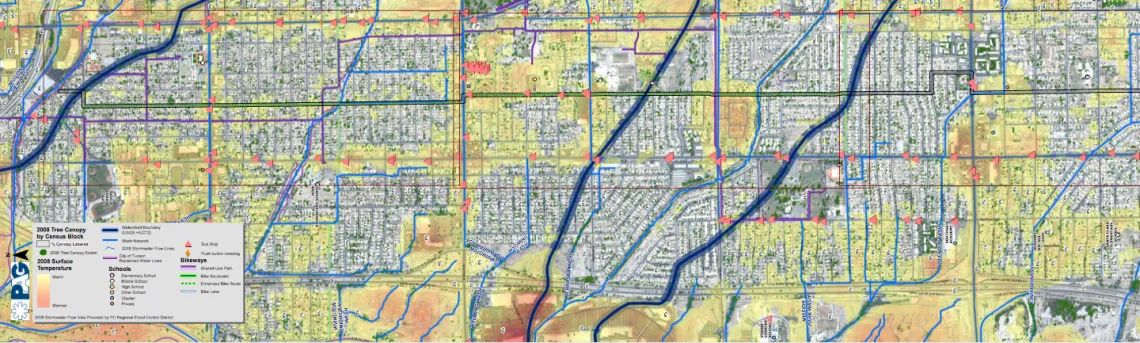

First, the City of Tucson’s Bike Boulevard Master Plan is designed to create a low-stress biking/walking-prioritized network throughout the city (including South Tucson), connecting schools, parks, libraries, neighborhoods, and a variety of services and everyday destinations. The Plan outlines the role of GI in the city’s plans to design bike boulevards, including use of native landscaping to help collect storm water and provide shade for people walking and biking.

Second, GI is a priority for urban heat island mitigation via urban greening under Plan Tucson, the City of Tucson General and Sustainability Plan, ratified by the voters in 2013. The plan emphasizes public participation in the planning, program, and project development, and identifies that “by initiating tree planting & storm water harvesting projects, lessening heat island effect, providing shade, & reducing flooding” (Tucson, 2013: 2.15), communities can be strengthened.

Finally, a basin study (which included four watersheds in the Airport Wash area that all drain directly to the Santa Cruz River) completed by Pima County in 2014, identified key areas of concern for controlling storm water. Watershed Management Group (WMG), a Tucson-based NGO promoting community-based and sustainable solutions to managing water resources, identified potential demonstration sites based on community drainage complaints, high flood depths and flood reduction benefits important for community resources such as schools, churches or community centers in their 2015 report titled Solving Flooding Challenges with Green Storm water Infrastructure in the Airport Wash Area. During the county’s study process, community leaders in El Vado, Santa Clara and Valencia neighborhoods, among others, expressed interest in low-cost green storm water infrastructure.

City of Tucson Mayor Jonathan Rothschild and City Council members Regina Romero (Ward One) and Richard Fimbres (Ward 5) are keenly interested in pursuing GI demonstration projects in the communities they represent. Mayor and Council requested the use of a portion of the Water Conservation Fund to develop a neighborhood-based storm water pilot program through Tucson Water. Tucson’s City Council recently approved a low-income residential water harvesting pilot program.

Community NGOs as part of this community-university partnership are engaged in efforts in southern Tucson. Tierra y Libertad Organization (TYLO) is a grassroots organization from southern Tucson with 16 years of experience engaging residents (youth in particular) in sustainability and food justice programs, and providing assistance with migrant rights. WMG led a neighborhood leaders training program in 2012 that included Elvira neighborhood leaders and focused on GI around residential and street-scape GI features. The Sonoran Institute (SI), a Tucson NGO is partnering with WMG and Udall Center researchers with Royal Bank of Canada’s Blue Water Project to fund demonstration projects situated in Airport Wash along the route.

Expected project benefits

We expect a variety of project benefits across an array of different scales.

First, in terms of on-the-ground improvement, we expect significant ecological and human benefits for the communities. These benefits include reduced storm water runoff and flood risk due to water harvesting, as well as reduced storm water pollution due to natural filtration, reduced heat stress due landscaping and shading, improved walkability and connectivity to the rest of the city, enhancing native habitat and biodiversity, and improved air quality. We might expect to find residential energy savings resulting from landscaping and shading, and perceptions of enhanced property values associated with GI and landscaping.

Second, we expect significant community benefits of interconnectedness and trust along with civic engagement, as well as neighborhood vibrancy. We will set the stage for the creation of a “friends of the greenway” organization that provides maintenance to the greenway, while facilitating communication between government officials and community representatives.

Taken together, these environmental and human benefits of GI provide a suite of ecosystem services that should contribute to the resilience and well-being of the communities. Beyond these communities in southern Tucson, this project can serve as a model for community GI projects that addresses equity in other Tucson communities and elsewhere in Arizona. City and county staff, university actors and community organizations will come to learn more about best processes and strategies for community engagement.